The article explains:

Dr Tisherman’s EPR process, developed with the help of $800,000 from the Department of Defence, is mostly about resurrection. The idea at this stage is to use equipment like the catheters and pumps that can be found in any trauma centre to suspend the life of critically injured people in order to buy more time for surgeons to try to save them.I'm encouraged by this kind of medical advance. One interesting quote from the article:

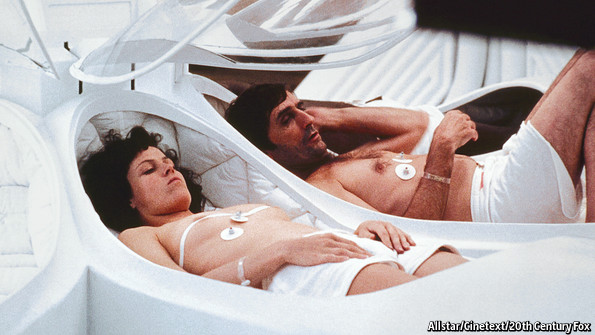

EPR works by lowering the patient’s body temperature and replacing their blood with a cold saline solution. Hypothermia is already induced in patients to help reduce bleeding during some surgical procedures. But cooling the body down so that it goes into a suspended state has not been tried before. The idea came from observations that people have been resuscitated having stopped breathing for half an hour or more after falling into icy water.

The Food and Drug Administration decided the procedure was exempt from informed consent, as patients would be too ill to give it themselves and might benefit because they were likely to die as no other treatment was available. For now, the patient has to be between 18 and 65 years old, have a penetrating wound, such as a knife, gunshot or similar injury, suffer a cardiac arrest within five minutes of arrival in the hospital and fail to respond to usual resuscitation efforts.Given that these patients would like die anyways without the experimental treatment (and that they presumably want to live), one can make a much stronger case for waiving the usual informed consent in this kind of emergency than in the more-controversial UK experiment (which involves giving standard adrenaline therapy vs. placebo to cardiac arrest patients.)

For more on the latter topic, see my recent Forbes piece, "UK To Experiment on Cardiac Arrest Patients Without Their Consent".